| | ||||

Published: Vintage 2010.  Originally published: Scribner's, 1911.  Published: Macmillan, 1985.  Published: Vintage, 2011. November, 2012  Published: Vintage, 2000. November, 2012  Published: John MUrray, 2010. November, 2012  Published: Penguin Random House, 2019. |

|

Recommended reading for all market fundamentalists and competition worshippers, and their high priests and acolytes. A witty, scholarly and nuanced account of the financial shenanigans leading up to the GFC. There are no villains, but plenty of smart dopes who follow other dopes on the basis that if everyone is a dope, one won't be punished for being a dope. But the dopes were rewarded with taxpayer-funded bailouts, so they must have been smart after all. It's all happened before, as John Cassidy's sense of history, and lucid exposition of economic ideas reveals. An understandable choice by Tom Stoppard for one of the "best books of 2010" in The Guardian Weekly, of 17th December 2010. Published: Penguin, 2009.  The God Delusion is not recommended for rationalists who want their rationalism to be rational. Having set up "the God hypothesis" for demolition, Dawkins proceeds to discuss issues that are largely peripheral to his general hypothesis, by more-or-less regarding his hypothesis as confirmed simply by a vigorous attack on the account of God we find in the the Old Testament of the Bible.

Haffner has a gift for pithyness. For example, taking the view that Hitler had an instinctive understanding of the weakness of his opponents, he comments on those who were surprised at Hitler's "miraculous" rapid victory over France in 1940, an attitude held by many owing to the defence by the French of their country in World war I: "the miracle was the defence in the first war". He considers that Hitler's experience of the chaotic revolutionary period in Munich in 1918-19 is of crucial importance to understanding Hitler's later attitudes and actions. Clarity of thought, writing and argument, as well as an underlying humanity, make this book compelling to read. Edward Crankshaw is quoted as saying about this book: "a quite dazzlingly brilliant analysis". Christopher Hitchins makes similar comments about Haffner's work in his review of Ian Kershaw's biography of Hitler. These comments are justified. Haffner's book was originally published in German in 1978, and in English in 1979. Its German title can be translated as "Notes on Hitler" which, while more subdued, seems more appropriate than the title used here. This edition is published by Phoenix, London, 2007, translated by Oliver Pretzel.

Published: . |

|

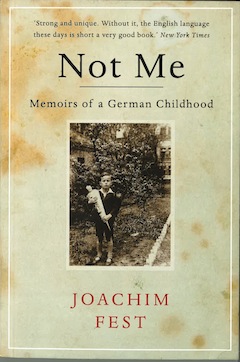

Published: Faber, 2010.  A remarkable book, with insights on every page. Niehbuhr has a talent for perception with cogency. Many of his observations have even greater relevance today, when what he calls "technics" and associated attitudes are markedly more pervasive in American (and western) society that when he wrote. His notion of irony in American history?: "....The triumph of 'common sense' in American history is thus primarily the triumph of the vitality of our democratic institutions. The ironic feature in it consists of the fact that we have achieved a tolerable synthesis between two conflicting ideologies in practice while we allowed the one to dominate in theory." It might be argued that such ironies are created by discrepancies that cannot be officially acknowledged, because society needs illusions to function and to validate itself to itself, perhaps particularly in the USA. And, it may be, as the author of the introduction, Andrew J. Bacevitch, claims, the most important book ever written on US foreign policy. But the book is not about foreign policy per se but about attitudes and culture in US society, and the contradictions and irony resulting from a tension between a high ideological rhetoric and sense of divine mission, and reality. But Niebuhr does not regard such tensions as stable, so that more recent technical and cutural developments, leading to a renewed emphasis on ideology, with consequent events, surely would not have surprised him. Originally published: Scribner's 1952. Edition reviewed here: University of Chicago Press, 2008.  I saw this "video installation" in January 2011 at the Art Gallery of South Australia. It's "The Feast of Trimalchio", a remarkable work by the Russian collective AES+F. It seduces, mesmerises and overwhelms with its beauty, its atmosphere of ritual, and its accompanying "story". True, its beauty is more that of a fashion magazine or a luxury hotel than that of Rembrandt or Corot, say; but that's deliberate and part of its irony, satire and "message". And what is its "message", if there is one and one can call it that? Well, it is more complex and ambiguous than initially appears, and I fear that one is inclined to read into it one's own predilections and concerns, especially as it has a very marked element of political and social comment. The booklet at the gallery about the work of AES+F was called by the rather foolish title "let the revolution begin". Is it a revolution to overthrow the shallowness and spiritual emptiness of western society, or is it a call to arms for fashion houses and luxury hotels to take over the world? For me, the former prevails, and "The Feast of Trimalchio" remains as a memento mori, not just of physical death, but of the possibility of the living death of the spirit and the soul. The overall mesmeric effect is heightened by the stately, sad and yearning music of the allegretto of Beethoven's seventh symphony, under the direction of Sir Roger Norrington. View Part I of "The Feast of Trimalchio" on youtube.  Joachim Fest's Not Me (2006) is one of the most interesting books I have read in many years. I was aware from a variety of sources of the the treatment of German Jews under Nazism but was less well informed how the rest of the population fared. In telling the story of his family, Fest provides an answer to the question posed by Richard J. Evans in his The Third Reich in Power (2005) : " How did the Nazis win over the hearts and minds of Germany's citizens, twist science, religion and culture, and transform the country's politics to achieve total dominance so quickly ?". Fest was a gentile German born in 1926 into a conservative Roman Catholic family living in a Berlin suburb. His father was a devout Christian who supported the Weimar republic, refused to join the Nazi Party and kept his sons out of the Hitler Youth until membership became compulsory in 1939. Fest's family paid the price for this principled stand and his father lost his teaching position for daring to criticise the Nazi regime. In December, 1944 Fest turned 18 and decided to enlist in the Wehrmacht to avoid being conscripted into the Waffen SS. His brief military service ended when he became a POW in France. After the the war and university studies he was a German historian, journalist, critic and editor and was a leading figure in the debates about the Nazi period until his death in 2006. In Not Me Fest concludes that it was not policy positions which brought the Nazis to power but the problems experienced by individuals. These included inflation, the world economic crisis and the collapse of the middle classes on whom the stability of the state depended. There were totalitarian or at least dictatorial regimes in a number of countries in the 1930s and Fest observes that the most obvious explanation for the success of National Socialism was that it attracted opportunists, like all groups endowed with funds and ready to use force. Fest recalls his father's belief that it was Hitler's accession to power "halfway legally" which blunted opposition. There were no general strikes which would have been called if the Nazis had seized power in a coup. The republican leadership was confused because the law seemed to be against them - "as proper Germans, upholding the law was more important to them than right or wrong". Stalin joked during the 1930s that if German revolutionaries travelled by train to a riot they would return home without striking a blow if no one was there to take their tickets. Not Me is an eminently readable book in which the results of Nazi ideology and policies are shown in the life of a German middle class family. © James Moore Published: . December, 2012 GO TO THE HOME PAGE EMAIL: nillsen@uow.edu.au |